Let’s talk about the 1%. No, not that 1%. Not “the top 1%” wealthiest people, a phrase popularised by the Occupy Wall Street Movement. I mean a different 1%.

The world is heading for a baby bust, and it has a lot to do with the 1% – the nearly 1% drop in the global total fertility rate (TFR) that’s occurred annually between 1960 and 2018.

It’s a figure that’s likely to have a huge socio-economic impact on Australia in the future, and it’s just one of many troubling ‘1%’ fertility stats.

According to Count Down, a new book by award-winning reproductive epidemiologist Shanna Swan, there has been a “1% effect” across a whole spectrum of fertility issues in Western countries.

Each year, we’re seeing a 1 percentage point:

- Drop in sperm counts;

- Decrease in testosterone levels;

- Increase in testicular cancers; and

- Rise in miscarriages.

All these trends are seriously affecting our ability to reproduce, and the most worrying thing is that some show no signs of levelling off. For example, sperm counts have dropped 50% over the last 40 years, and the rate of decline isn’t slowing down.

It’s not just men with fertility struggles; aspiring mothers face their own struggles. One Danish study found that the average twentysomething woman in the country today will find it harder to fall pregnant than her grandmother did in her mid-30s.

An infertile world?

Swan says if the situation doesn’t change, we’re on course for a largely infertile world by 2045, with most couples needing to use IVF and other assisted reproduction techniques to have children.

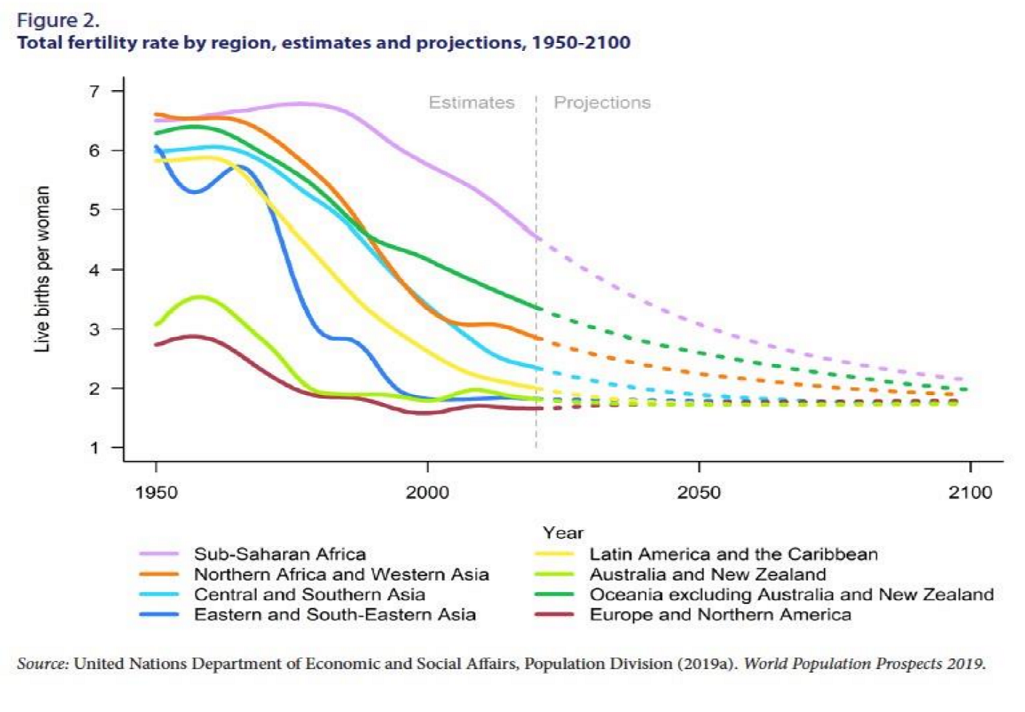

As we can see from the graph below, the TFR is predicted to continue dropping across multiple regions over the coming decades.

From World Fertility and Family Planning 2020 by UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, ©2020 United Nations. Reprinted with the permission of the United Nations.

This isn’t a problem that’s far off in the distance. I’m a mother to two young children, and they’ll still be in their 20s when the world becomes largely infertile -assuming Swan’s timelines are accurate.

That’s a terrifying thought for me and, I’m sure, for many other parents and grandparents. Not least because infertility can have severe mental health repercussions for both men and women.

What’s causing these infertility issues? Well, we don’t exactly know. Birth rates are obviously affected by social trends, such as people choosing to have kids later in life – or not at all. But this is unlikely to be causing lower sperm counts or falling testosterone levels!

Swan believes endocrine disruption is the main culprit. Essentially, environmental toxins are wreaking havoc on our body’s hormonal systems (and reproductive capabilities). Chemicals in plastics, pesticides, cosmetics and even food have been shown to cause endocrine disruption.

Now, Swan recently admitted it’s “speculative to extrapolate” on current infertility trends, but the research is persuasive. And Australia hasn’t escaped the fertility crisis.

In 1961, Australian women had 3.5 children on average. By 2018, this figure stood at just 1.7.

Along with many other countries, Australia has fallen below the replacement fertility rate of 2.1. In other words, not enough babies are being born to replace the number of people who are dying, leading to a declining population.

This is already happening. Australia’s population shrunk for the first time since World War 1 in the third quarter of 2020.

It would be disingenuous for me to suggest that’s entirely because of fertility issues, of course. Border closures due to Covid-19 have significantly restricted immigration levels, a major driver of Australia’s population growth.

On the other hand, perhaps this merely emphasises how immigration figures have been concealing the country’s steadily declining birth rate, until now.

Why does this matter?

Last year, Stanford University economics professor Charles Jones modelled some of the possible outcomes of population decline in his ominously titled ‘The End of Economic Growth?‘ paper.

The upshot? He predicts that vanishing populations will lead to less innovation, minimal economic growth and a stagnation in living standards at a global scale. This paints a pretty bleak picture.

Admittedly, the true economic impact of declining populations is difficult to forecast accurately. One aspect of this seems to be clear, however, there will be a dramatic shift in national demographics over the coming decades if current trends continue. Put simply, there will be a far greater number of retirees than working-age people.

Covid-19 has accelerated these demographic trends, with the Australian economy estimated to be 5% smaller – permanently – than pre-Covid forecasts due to a population slump of approximately 4%. That is the equivalent of 1 million Australians.

Famed demographer Bernard Salt recently wrote an article on the topic of Australia’s baby bust, in which he explained how the transitioning of the baby boomer generation into retirement is coinciding with the fallout of the pandemic.

Salt predicts this may cause problems for politicians, business leaders and bureaucrats, as they will face a more vocal, energetic, and active population of retirees.

It will also be the first time in Australia (and other countries) that such a large group of older people will need to be supported by a far smaller cohort of workers.

Working together

That the trends Mr Salt identifies are occurring against a backdrop of plunging fertility rates should give us even more cause for alarm. According to Dr Swan, the current trend of declining sperm counts could leave half of the Western male population impotent by 2045. That prospect is terrifying on its own before we consider these additional structural headwinds.

Thus, like Mr Salt, I agree there are challenges ahead for Australia in a world where the ratio of workers to retirees will become heavily skewed in favour of the latter.

However, I also believe there are a lot of reasons to be optimistic. First, we have excellent healthcare and superannuation systems, which should offset a lot of the pressure that most ageing nations face.

Second, I don’t think more people holding off retirement is a bad thing. In fact, I think it is possibly a solution. We should actively be encouraging over-65s to remain in the workforce.

Retiring in your mid 60s may have made sense in decades past, when people weren’t expected to live a long and healthy life post-employment, but this clearly isn’t the case today. Men aged 65 between 2016-18 will live another 20 years on average, while women of the same age could expect to live another 22 years.

The skills, experience, and mentorship abilities this generation possesses is invaluable to businesses. After all, we are going to need every bit of expertise at our disposal to continue driving innovation forward in the future.

As for solving the fertility crisis, that is a bit beyond my expertise! However, it will likely require co-ordinated efforts at the national level. If chemicals are to blame, finding safer substitutes (and introducing new regulations) could be a part of the solution. If its obesity and diet, then that will need to be the focus.

And if you want to make personal changes that boost your reproductive health, Swan has some tips: eat a Mediterranean diet (certified organic if possible), keep active, reduce your stress levels, and lower the chemical footprint in your home.

That is probably good advice for everyone, not just prospective parents.

Emma Davidson is Head of Corporate Affairs at London-based Staude Capital, manager of the Global Value Fund (ASX:GVF). This article is the opinion of the writer and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.